- HOME

- ABOUT ME

- movies

- MEDIA

- L.Onerva

- Eino Leino

- Eeva-Liisa Manner

- Erään Opon päiväkirja

- Elämänkenttäni

- Elämäni ”viiva”

- Käyttöteoriani – se miten minä ohjaan

- Kulttuuritietoinen ja kansainvälistyvä ohjaus

- Ohjauksen järjestäminen maahanmuuttajakoulutuksessa

- Ohjauksen yhteiskunnallinen viitekehys

- Ohjaukäsite

- Oma opiskeluorientaatio

- Opiskelijoiden yksilöllisyys ohjauksessa

- EETTISET KYSYMYKSET

- Psykososiaalisen kehityksen teoria

- Suhteeni erilaisuuteen ja tehtäväni opinto-ohjaajana

- Opinto-ohjauksen ja erityisopetuksen yhtäläisyyksiä ja eroja

- Kehitykseni opinto-ohjaajana

- Maahanmuuttajan uraohjaus

- Maahanmuuttajien ohjaus ja neuvonta: kuka, mitä, miten?

- Ohjauksen tulevaisuus

- Elämänkenttäni

- Mariana Marin

- Claudiu Komartin

- Mariana Codrut

- Roland Erb

- Romanian poetry

- ESSAYS

- STORIES

- CLASSIC POETRY

- CONTEMPORARY POETRY

- TRANSLATED POEMS

- READING POETRY

- CONTACT

- translated Italian-English

- translated Italian-Romanian

- translated Spanish-English

- translated Spanish-Romanian

July, 2023

O caldă înțelegere umană / A warm human understanding

POSTED IN Mariana July 28, 2023

O caldă înțelegere umană / A warm human understanding

Totul este atât de departe,

încât sentimentele și-ar declara singure

legea marțială.

Aici nimeni nu te poate salva.

Dimineața stau de vorbă cu bătrânul Kolea,

– basarabeanul de o sută de ani din inima câmpiei.

Prin fumul gros lăsat de pipele noastre

cuvintele au mai găsit câte o amintire

înfiptă în coapsa vocabularului.

Vorbim despre mugurii calzi și grădinărit,

despre exilul morții de la un anotimp la altul,

despre războiul care amușină în jurul castelului de apă,

despre sensibilitatea ultragiată și despre limba română.

Bătrânul Kolea nu mai are nimic de pierdut.

Eu pierd zilnic totul.

Poate de aceea ne înțelegem atât de bine

când acceleratul de 8 este inundat de o caldă înțelegere umană

și trece el sfios, acceleratul,

prin carnea de o sută de ani,

prin stupii harnici care pot șterge la cer

urmele oricărei crime,

prin hohotul care de-abia mă mai rabdă.

– Sigur că vine o vreme

când trebuie să-ți recapeți demnitatea,

– murmură pedagogic bătrânul Kolea, basarabeanul.

A devenit vinovată trecerea sub tăcere

a numărului de morți de la Dachau și Auschwitz?

A deveniiit…

Să fremătăm atunci de bucurie

tu, spirit,

și tu, hoit!

Poate se va vorbi într-o zi

și despre adevărul acesta

aidoma unei condicuțe ieșită noaptea

să ațâțe gunoiul cât muntele de mare,

cât neputința și bestialitatea ei.Mariana MARIN

……………..

A warm human understanding

Everything is so far away

that the feelings would declare their own

martial law.

No one can save you here.

In the morning I talk with the old man Kolea,

– the hundred-year-old Bessarabian from the heart of the plain.

Through the thick smoke left by our pipes

the words found one more memory

embedded in the thigh of the vocabulary.

We talk about warm buds and gardening,

about the exile of death from one season to another,

about the war sniffing around the water castle,

about the offended sensibility and about the Romanian language.

Old Kolea has nothing left to lose.

I lose everything daily.

Maybe that’s why we get along so well

when the 8 o’clock fast train is flooded with a warm human understanding

and it passes timidly, the fast train,

through the one hundred years flesh,

through the industrious beehives that can erase on the sky

the traces of any crime,

through the roar that can hardly stand me anymore.

– Of course there comes a time

when you have to regain your dignity,

– old Kolea the Bessarabian murmurs pedagogically.

Has become culpable the keeping under wraps of the death toll at Dachau and Auschwitz

It becaaame…

Let us tremble with joy then,

you, spirit,

and you, corpse!

Maybe it will be spoken one day

about this truth also,

like a prostitue who goes out at night

to stir up the garbage as big as the mountain,

as her helplessness and bestiality.trad. M. M. Biela

Leprozeria / The leper colony

POSTED IN Mariana July 28, 2023

Leprozeria / The leper colonyAveai dreptate, Sebastian Reichmann!

Ne trăiam scalpul cu aceeași ferocitate

pe care am putea-o bănui în burțile copiilor africani.

Ne despărțim mereu de ceva.

O țesătură ușoară de obsesii,

un vânticel de răsărit cu spahii,

o piatră țâșnind din senin

în trenul care te poartă, te poartă

…și pare de-ajuns:

Bolile sociale, aidoma bolilor de piele,

proliferează subtil.

La 1956 nu s-ar putea spune

că Europa nu avea pentru mine

un oarecare mister.

Lupta dintre contrarii

gâfâia pe aproape așteptându-mă,

așteptându-te, vrându-ne vii…

Dar ce poate fi mai frumos

decât o copilărie tăiată mărunt

care să îmblânzească în timp hrăpăreața memorie!Ce bine e să stai mai târziu

cu un ghemotoc de hârtie lipit de cerul gurii:

„Du-te! Du-te!

Palidă și foarte tristă

ești prea goală

pentru veacul eunuc!”

Oricum, de la crima de atunci

la cinismul ei de acum

cărțile morților

au licitat viețile sfinților

și ai învățat să pierzi.

Mariana MARIN…………………

The leper colony

You were right, Sebastian Reichmann!

We were experiencing our scalps with the same ferocity

that we might suspect in the bellies of African children.

We always part with something.

A light fabric of obsessions,

an easterly breeze with spahis,

a stone springing out of nowhere

in the train that carries you, carries you

…and it seems enough:

Social diseases, like the skin diseases,

subtly proliferate.

In 1956 it could not be said

that Europe didn’t have some mystery

for me.

The fight between opposites

was panting nearby waiting for me,

waiting for you, wanting us alive…

But what could be more beautiful

than a childhood chopped up

to tame in time the rapacious memory!How good it is to sit later

with a paper ball stuck to the roof of the mouth:

“Go! Go!

Pale and very sad

you are too empty

for the eunuch age!”

Anyway, since the crime of then

to her cynicism of now

the books of the dead

auctioned the lives of the saints

and you have learned to lose.

trad. M. M. Biela

cerul-diamant / the diamond-sky

POSTED IN Mariana Codrut July 28, 2023

cerul-diamant / the diamond-skyînăuntru vedeai

prin piele, prin pléoape

– un cer cald, lichid

te ținea aproape.nu știai de nu

cînd te-au smuls. au zis:

”și-n cerul de afară

să te scalzi ți-e scris!”.dar, orbitor și rece,

el taie-n carne vie.

o bucată lui,

o bucată ție,

o bucată lui,

o bucată ție…Mariana CODRUT

…………..

the diamond-sky

inside you could see

through skin, eyelids through

– a warm, liquid sky

that close held you.of no you did not know

when snatched you’ve been.’twas said:

“in the sky outside

to bathe is your fate!”but, blinding and cold,

living flesh he cuts through

one piece for him

one piece for you

one piece for him

one piece for you…trad. M. M. Biela

Sufletele mele-s doua / My souls are two

POSTED IN classic poetry, Romanian July 26, 2023

Sufletele mele-s doua / My souls are two

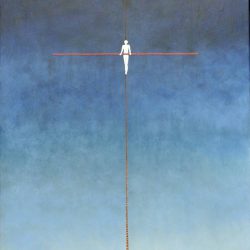

Sufletul mi-e un jucator pe sfoara.

Dar sufletele mele-s doua.

Unul intinde sfoara si o desfasoara

Necontenit, taioasa, vie, noua,

Si celuilalt «ridica-te si du-te»-i spune,

Si celalalt, rinjind i se supune.

Ochii acestuia de fiara sint

Si-l gauresc uitindu-se-n pamint

Si seaca apa si-ard pe sus

Soimii de vii, in zborul din apus.Monstrul din aer poate sa se lase

Purtat in bici pe firul de matase,

Cu talpa lui de piatra si pamint,

Parca purtat si leganat de vint.

Scrisneste.

S-a oprit.

Nu-i dau ragaz.

Biciul meu greu ii cade pe grumaz,

Pe umere, pe pulpe, pe picioare.

Racneste, urla, vrea sa se scoboare.Nu-i nici-o clipa de repaos.

Arunca-te si cazi in haos,

Si ametit, precipitat in el,

Sfarima-ncuietoarea de otel.

Tudor ARGHEZI

……………….

My souls are two

My soul is tightrope walker thru.

But my souls are two.

One stretches out the rope and unwinds it

Unceasingly, sharp, alive, new,

And tells the other “get up and go”,

And the other, grinning, does so.

His eyes are beast-like bound

While watching they are piercing the ground .

And they dry the water and burn in sight

The falcons alive, in their sunset flight.The monster in the air itself could let

Be whipped along the silken thread,

With its sole of stone and clay

As if by wind carried and swayed.

Grinds.

Stops.

I don’t give him a break.

My whip falls heavily on his neck,

his shoulders, his thighs, on his feet.

He roars, he shouts, he wants to descendThere is not a moment of rest or pause

Throw yourself and fall into the chaos,

And dizzy, plunged into havoc,

Shatter and break the steel lock.trad. M. M. Biela

Opowiadanie o starych kobietach / A story of old women / O poveste despre batrane

POSTED IN classic poetry July 25, 2023

Opowiadanie o starych kobietach / A story of old women / O poveste despre batrane

Lubię stare kobiety

brzydkie kobiety

złe kobietysą solą ziemi

nie brzydzą się

ludzkimi odpadkami

znają odwrotną stronę

medalu

miłości

wiaryprzychodzą i odchodzą

dyktatorzy błaznują

mają ręce splamione

krwią ludzkich istotstare kobiety wstają o świcie

kupują mięso owoce chleb

sprzątają gotują

stoją na ulicy z założonymi

rękamimilczą

stare kobiety

są nieśmiertelneHamlet miota się w sieci

Faust gra rolę nikczemną i śmieszną

Raskolnikow uderza siekierą

stare kobiety są

niezniszczalne

uśmiechają się pobłażliwieumiera bóg

stare kobiety wstają jak co dzień

o świcie kupują chleb wino rybęumiera cywilizacja

stare kobiety wstają o świcie

otwierają okna

usuwają nieczystościumiera człowiek

stare kobiety

myją zwłoki

grzebią umarłych

sadzą kwiaty

na grobachlubię stare kobiety

brzydkie kobiety

złe kobietywierzą w życie wieczne

są solą ziemi

korą drzewa

są pokornymi oczami zwierząttchórzostwo i bohaterstwo

wielkość i małość

widzą w wymiarach właściwychzbliżonych do wymagań

dnia powszedniegoich synowie odkrywają Amerykę

giną pod Termopilami

umierają na krzyżach

zdobywają kosmosstare kobiety wychodzą o świcie

do miasta kupują mleko chleb

mięso przyprawiają zupę

otwierają oknatylko głupcy śmieją się

ze starych kobiet

brzydkich kobiet

złych kobietbo to są piękne kobiety

dobre kobietystare kobiety

są jajem

są tajemnicą bez tajemnicy

są kulą która się toczystare kobiety

są mumiami

świętych kotówsą małymi

wysychającymi źródłami

pomarszczonymi owocami

albo tłustymi

owalnymi buddamikiedy umierają

z oka wypływa

łza

i łączy się

na ustach z uśmiechem

młodej dziewczyny

Tadeusz Różewicz

……………………

A STORY OF OLD WOMEN

I like old women

ugly women

mean womenthey are the salt of the earth

they don’t abhor

human wastethey know the flipside

of the coin

of love

of faithcoming and going

dictators fool around

their hands are stained

with human bloodold women get up at dawn

they buy meat fruit bread

clean cook

stand on the street

arms foldedsilently

old women

are immortalHamlet is thrashing around in the net

Faust plays a wicked and ridiculous role

Raskolnikov strikes with an axeold women are

indestructible

they smile indulgentlygod dies

old women get up like every day

at dawn they buy bread wine fishcivilization dies

old women get up at dawn

open the windows

remove the filtha man dies

old women

wash the corpse

bury the dead

plant flowers

on the gravesi like old women

ugly women

mean womenthey believe in eternal life

they are the salt of the earth

Tree bark

the humble eyes of animalscowardice and heroism

greatness and pettiness

they see the right perspectiveclose to the demands

of everyday lifetheir sons discover America

perish at Thermopylae

they die on the cross

conquer the spaceold women go out to the city at dawn

to buy milk bread meat

to season the soup

they open the windowsonly fools laugh

at old women

ugly women

mean womenfor they are beautiful

good womenold women

they are an embryo

a mystery devoid of mystery

a rolling sphereold women

are the mummies

of sacred catsthey are either small

drying springs

wrinkled fruit

or plump

oval buddhaswhen they die a tear

flows from the eye

and joins

on the lips

with the smile

of a young girl.

………………..

O poveste despre bătrâne

Îmi plac bătrânele

femei urâte

releele sunt sarea pământului

ele nu detesta

deșeul uman

ele cunosc reversul

medaliei

al dragostei

al credinţeivin și pleacă

dictatorii care fac pe clovnii

cu mâinile pătate

de sângele-omenescbătrânele se trezesc în zori

cumpără pâine fructe carne

fac curatenie gatesc

stau în stradă cu bratele incrucisatetacute

femeile bătrâne

sunt nemuritoareHamlet se zbate în plasă

Faust joacă un rol răutacios și ridicol

Raskolnikov lovește cu un topor

femeile bătrâne sunt

indestructibile

ele zâmbesc îngăduitoareDumnezeu moare

bătrânele se trezesc ca în fiecare zi

în zori cumpără pâine vin peștecivilizația moare

bătrânele se trezesc în zori

deschid ferestrele

îndepărtează murdariamoare un om

bătrânele

spală cadavrul

îngroapă mortul

plantează flori

pe morminteimi plac femeile batrane

femei urâte

femei releele cred în viața veșnică

sunt sarea pământului

scoarta copacului

sunt ochii umili ai animalelorlașitate și eroism

măreție și micime

ele văd prin prisma potrivitasimilara cerintelor

vietii de zi cu zifiii lor descoperă America

se pierd la Termopile

mor crucificati

cuceresc universulbătrânele pleaca în oras de cu zori

cumpără lapte pâine carne

condimenteaza supa

deschid ferestrelenumai prostii rad

de femeile bătrâne

femei urâte

femei relepentru că sunt femei frumoase

femei bunefemei bătrâne

sunt un embrion

sunt un mister fara de mister

sunt o minge care se da de-a durafemeile bătrâne

sunt mumiile

pisicilor sfintesunt fie mici

izvoare uscate

fructe încrețite

sau buddha gras

si ovalcând mor, o lacrima

curge din ochi

și se uneste

pe buze cu zâmbetul

unei fete tinere.

trad. M. M. Biela

Săptămâna Patimilor / The Holy Week

POSTED IN Mariana July 19, 2023

Săptămâna Patimilor / The Holy Week

Duioasă fericire și liniște a cărnii

într-o dimineaţă de odihnă;

și, deodată, amintirea rapiţei

și a elevului K.: „Dacă au semănat porumb

de ce a ieșit atâta rapiţă?”

O Săptămână a patimilor luminată

de o Noapte a Sfântului Bartolomeu

și un fel de păpușă mecanică, rasă în cap,

un fel de gură de câine: „Veniţi de la Poarta Albă?”

Astfel poate începe senzaţia aceea de gol

care anunţă venirea ficţiunii.

Ea trece la numai trei pași de casa ta

și tu îi adulmeci prin aer securea mătăsoasă,

vibraţia semnelor, carnea care i se desprinde încet.

Elevul K. și gura de câine își pot schimba rolurile

și toate sub ochii tăi,

acoperiţi de grămezi nesfârșite de rapiţă…Tu însăţi schimbi dubioasa zi de odihnă legală

cu ecoul livresc al Nopţii Sfântului Bartolomeu;tu însăţi treci mai târziu

la numai trei pași de casa ta,

adulmecând prin aer o băltoacă mătăsoasă,

prin viaţa ta, gură de câine,

păpușă mecanică,

rasă în cap.

Mariana MARIN

…………………..The Holy Week

Sweet bliss and peace of flesh

on a restful morning;

and, suddenly, the memory of rapeseed

and of student K.: “If they sowed corn

why did so much rapeseed come out?”

A Holy Week illuminated

by a Night of St Bartholomew

and a kind of mechanical doll, shaved head,

a kind of dog’s mouth: “Have you come from the White Gate?”

Thus can begin that feeling of emptiness

that heralds the arrival of fiction.

It passes only three steps from your house

and you sniff its silky ax through the air,

the vibration of the signs, its slowly peeling of flesh.

Student K. and the dog’s mouth can switch roles

and all before your eyes,

covered with endless piles of rapeseed…You yourself exchange the dubious legal day of rest

with the bookish echo of St Bartholomew’s Night;thou thyself pass’st later

only three steps from thy home,

sniffing through the air a silky puddle,

through thy life, dog-mouthed,

mechanical doll,

shaved head

trad. M. M. Biela

Pumaho

POSTED IN Mariana July 15, 2023

Pumaho

Refuz să mai privesc realitatea în față.

Port în brațe doar poemul acesta

care miroase urât – câine mort.

Îl pocnesc și bucăți de carne

sar din râsul hidos.

Plec atunci la marginea mării să mă spăl.

El îmi sare în față

și mă trezesc în hainele de luni

funcționar tăcut,

spoind lumea cu literele unui alfabet

singuratic și mort.

– Trebuie notat totul, îmi șoptește

manșeta mea roasă de viață.

Inventează acolo unde ochii îți cad înaintea plânsului

și limba se desfată înainte de râs.

Îmi iau atunci sfertul de secol în spate

și, iată, notez:

„La întretăierea drumurilor comerciale

se poate muri prin utopie sau uitare de sine.

O lume brutală, ai spune,

dacă anumite previziuni nu te-ar mai fi dus cu vorba

din epoca ming și te-ar fi părăsit în epoca tao.

La intrarea în muncile de primăvară

mâinile umflate ale copiilor sugrumă ardeiul gras

cu dexteritatea unui mecanism social

și pe cer e numai fum.

Apoi devine o obișnuință.

Mirosul prostiei?

Imaginați-vă

(aici naratorul e alb și tremură

în fața memoriei sale clevetitoare)

carnea a o sută de oi

sub roțile a 21 de vagoane de tren.

Ehei, cum ți-ai mai salva atunci pielea

într-o tăbăcărie umedă,

hohotind sub iarba înaltă!La întretăierea drumurilor comerciale

memoria scapă esențialul, ca într-un fel

de uriașă măcelărie unde mirosurile

se destind și pe cer e numai fum.Trebuie notat totul, spunea

manșeta mea roasă de viață.

La întretăierea acestei lumi

cu imaginea sa despre sine

am privit realitatea în față.

Am fost la marginea mării să mă spăl.

Ochii mi s-au înnegrit înaintea plânsului.Limba mi s-a înverzit înaintea ierbii.

Sfertul de secol a simțit mirosul prostiei

și într-un târziu dexteritatea unui mecanism social

mi-a căzut la picioare și mi-a șoptit:

– Trebuie notat totul

chiar dacă mă pocnești

în această uriașă măcelărie

unde mai crezi că te poți salva,

printre hălci de ardei gras,

unde ai visat și ai scris

ca o manșetă roasă de viață,

unde ai chicotit cu fusta-nstelată

când mirosurile se destind și pe cer e numai fum…Mariana MARIN

…………………..

Pumaho

(10 a.m. and 3 p.m. at obor station)

I refuse to face reality anymore.

I hold only this poem

that stinks – dead dog.

I slap him and chunks of flesh

jump from the hideous laughter.

I then go to the edge of the sea to wash myself.

He jumps in front of me

and I wake up in Monday’s clothes

silent clerk,

whitewashing the world with the letters of a lonely and dead

alphabet.

– Everything must be written down, whispers to me

my worn by life sleeve.

Invent where your eyes fall before weeping

and the tongue relishes before laughter.

I then take my quarter of a century on my back

and, here, I note:

“At the intersection of trade routes

one can die through utopia or self-forgetfulness.

A brutal world, you’d say

if certain predictions hadn’t talked you around

from the ming era and left you in the tao era.

When entering the spring field-work

the swollen hands of children strangle the bell pepper

with the dexterity of a social mechanism

and there is only smoke in the sky.

Then it becomes a habit.

The smell of stupidity?

Imagine

(here the narrator is white and trembling

before his slanderous memory)

the flesh of a hundred sheep

under the wheels of 21 train cars.

He-heeei, how would you save your skin then

in a wet tannery,

roaring in the tall grass!At the intersection of trade routes

the memory misses the essentials, like in some kind of

huge butcher shop where the smells

spread and there is only smoke in the sky.Everything must be written down, said

my worn by life sleeve.

At the intersection of this world

with its self-image

I looked reality in the face.

I went to the edge of the sea to wash myself.

My eyes turned black before the crying.My tongue turned green before the grass.

The quarter of a century smelled the stupidity

and at last the dexterity of a social mechanism

fell at my feet and whispered:

– Everything must be written down

even if you slap me

in this huge butcher shop

where you still think you can save yourself,

among chunks of bell peppers,

where you dreamed and wrote

like a worn by life sleeve,

where you giggled with the starry skirt

when the smells spread and there is only smoke in the sky…trad. M. M. Biela

Repetabila povară / The repeatable burden

POSTED IN classic poetry, Romanian July 14, 2023

Repetabila povară / The repeatable burdenCine are părinţi, pe pământ nu în gând

Mai aude şi-n somn ochii lumii plângând

Că am fost, că n-am fost, ori că suntem cuminţi,

Astăzi îmbătrânind ne e dor de părinţi.Ce părinţi? Nişte oameni ce nu mai au loc

De atâţia copii şi de-atât nenoroc

Nişte cruci, încă vii, respirând tot mai greu,

Sunt părinţii aceştia ce oftează mereu.Ce părinţi? Nişte oameni, acolo şi ei,

Care ştiu dureros ce e suta de lei.

De sunt tineri sau nu, după actele lor,

Nu contează deloc, ei albiră de dor

Să le fie copilul c-o treaptă mai domn,

Câtă muncă în plus, şi ce chin, cât nesomn!Chiar acuma, când scriu, ca şi când aş urla,

Eu îi ştiu şi îi simt, pătimind undeva.

Ne-amintim, şi de ei, după lungi săptămâni

Fii bătrâni ce suntem, cu părinţii bătrâni

Dacă lemne şi-au luat, dacă oasele-i dor,

Dacă nu au murit trişti în casele lor…

Între ei şi copii e-o prăsilă de câini,

Şi e umbra de plumb a preazilnicei pâini.Cine are părinţi, pe pământ nu în gând,

Mai aude şi-n somn ochii lumii plângând.

Că din toate ce sunt, cel mai greu e să fii

Nu copil de părinţi, ci părinte de fii.Ochii lumii plângând, lacrimi multe s-au plâns

Însă pentru potop, încă nu-i de ajuns.

Mai avem noi părinţi? Mai au dânşii copii?

Pe pământul de cruci, numai om să nu fii,Umiliţi de nevoi şi cu capul plecat,

Într-un biet orăşel, într-o zare de sat,

Mai aşteaptă şi-acum, semne de la strămoşi

Sau scrisori de la fii cum c-ar fi norocoşi,

Şi ca nişte stafii, ies arare la porţi

Despre noi povestind, ca de moşii lor morţi.Cine are părinţi, încă nu e pierdut,

Cine are părinţi are încă trecut.

Ne-au făcut, ne-au crescut, ne-au adus până-aci,

Unde-avem şi noi însine ai noştri copii.

Enervanţi pot părea, când n-ai ce să-i mai rogi,

Şi în genere sunt şi niţel pisălogi.

Ba nu văd, ba n-aud, ba fac paşii prea mici,

Ba-i nevoie prea mult să le spui şi explici,

Cocoşaţi, cocârjaţi, într-un ritm infernal,

Te întreabă de ştii pe vre-un şef de spital.

Nu-i aşa că te-apucă o milă de tot,

Mai cu seamă de faptul că ei nu mai pot?

Că povară îi simţi şi ei ştiu că-i aşa

Şi se uită la tine ca şi când te-ar ruga…Mai avem, mai avem scurtă vreme de dus

Pe conştiinţă povara acestui apus

Şi pe urmă vom fi foarte liberi sub cer,

Se vor împutina cei ce n-au şi ne cer.

Iar când vom începe şi noi a simţi

Că povară suntem, pentru-ai noştri copii,

Şi abia într-un trist şi departe târziu,

Când vom şti disperaţi veşti, ce azi nu se ştiu,

Vom pricepe de ce fiii uită curând,

Şi nu văd nici un ochi de pe lume plângând,

Şi de ce încă nu e potop pe cuprins,

Deşi plouă mereu, deşi pururi a nins,

Deşi lumea în care părinţi am ajuns

De-o vecie-i mereu zguduită de plâns.Adrian PAUNESCU

………………

The repeatable burden

Whoever has parents, on this earth not in thought

He still hears in sleep the eyes of the world sob

If we were, if we weren’t, or if we are kind,

Today we get older with our parents in mind.What parents? Some people who no longer can fit

By so many children and so much mistreat

Some crosses, alive yet, breathing harder and shy,

Are these parents of ours who always sigh.What parents? Some people there too, with some dreams

Who painfully know what each penny means.

Whether young or not, as their papers provide,

Doesn’t matter at all, they’ve turned grey and abide.

To see their child land a step higher and deep,

How much work, and torment, and nights with no sleep!

Even now, when I’m writing, as if screaming I’d bear,

I know them, I feel them, suffering somewhere.

We remember of them, after long weeks on hold

Old sons what we are, with our parents old

Did they buy firewood, do they ache in their bone,

Didn’t they die sad in their house alone…

Between them and children is a progeny of dread,

And the shadow of lead of our daily bread.

Whoever has parents, on this earth not in thought

He still hears in sleep the eyes of the world sob

For the hardest to be is of all that exists

Not a child of parents, but a parent of kids.

From the eyes of the world many tears have been wept

But for heavenly flood not enough weeping yet.

Do we still have parents? Do they still children have?

On this earth of crosses to be man not to crave.

By their needs humbled and with their head bowed

In a poor little town, in a village remote,

Even now they are waiting from their elders a sign ,

Or letters from children telling that they are fine,

Like some ghosts they come rarely out to the gates,

Talking only of us like some dear dead fates.

Who has parents alive isn’t lost yet, at last

Who has parents alive he still has a past.

They made us, they raised us, they brought us so far,

Where we have our own children and parents we are.

They may seem annoying, when there’s no more to give,

They may get on our nerves, that is the narrative.

Either blind, either deaf, either slow on their lane,

Either it takes too long to tell them and explain,

Hunch-backed and stooping like carrying a cross,

They ask if you know of a hospital boss.

Don’t you feel a deep, strange pity at all

For they can’t do a thing by themselves anymore?

That you feel them as burden and they know that it’s true,

And they look at you as if they’d beg of you…

We still have a short time to bear and to shrine

On our conscience the burden of this sacred decline

After that under skies we shall be very freed,

There will be less of those who don’t have and who need.

And someday the time comes when feel it we shall

That a burden we are for our children as well,

And only at a sad and not a distant day ,

When we’ll know with despair news not known today,

We’ll get why the children so soon do forget,

And they see not an eye in the world cry regret,

Why throughout the earth there is still no flood,

Even though it’s been raining, even though it has snowed,

Even though the world where as parents we’re trying,

For an eternity has been shaken by crying.

TO MY FATHER, rest in peace…

trad. M. M. Biela

Terapeutică din anii ciumei / Therapeutics from the plague years

POSTED IN Mariana July 13, 2023

Terapeutică din anii ciumei / Therapeutics from the plague yearsDacă pleca uneori din oraș

era pentru că viața ei devenise

un fel de cameră părăsită în grabă,

pe care o regăsești mai târziu

jefuită de dihania amintirilor pitice.

În locurile în care i se întâmpla să ajungă,

pe la răscruci,

se rupea ca o pâine caldă

și își lepăda pielea de șarpe.

Înregimentate, răutățile strânse

în vremea din urmă

se scurgeau în praful drumului

iar ea își privea trupul nou cu uimire.

Se bucura de el ca în noaptea

în care, bâjbâind în întunericul anilor,

o steluță îi luminase

literele unei limbi

ce știa de acum să o recunoască.

Dacă pleca uneori

era pentru că lumile se prăbușeau

cu prea multă viteză

în somnul ei chinuit;

și astfel,

ceea ce dimineața părea a fi

idee cu articulații coerente și fine,

noaptea era găsit gunoi măturat cu obstinație

și ascuns după ușă.

– Aceasta este soarta oricărei utopii,

să dispară într-o zi în propriul gunoi,

să fie uitată și-ascunsă

aidoma unei boli rușinoase;

să moară în propriul ei orgoliu

cu articulații de ciută,

coerente și fine,

– veneau să o liniștească

bărbile înțelepților.

Dar ea atunci trântea ușile și mai în grabă,

lăsa orașul în urmă

și își ferea și mai mult fața

de orice chip omenesc.

Se așeza (bunăoară) pe la răscruci,

cu părul în flăcări,

zobită mărunt de neputința gâlgâitoare

care-i țâșnea din gâtlej,

de nebunia cu chip uman

în care i se cerea să fie ciută,

doar ciută,

cu articulații coerente și fine.

Mariana MARIN………………..

Therapeutics from the plague years

If she sometimes went out of town

it was because her life had become

a kind of hastily abandoned room,

which you find later

robbed by the beast of dwarven memories.

In the places where she happened to end up,

at the crossroads,

she would brake like warm bread

and shed her snakeskin.

Registered, the evils gathered

in recent times

were dripping into the road dust

and she looked at her new body in awe.

She rejoiced in it as in the night

when, groping in the darkness of years,

a little star had illuminated

the letters of a language

she now knew to recognize.

If she left sometimes

it was because worlds were collapsing

too fast

in her tormented sleep;

and thus,

what in the morning seemed to be

an idea with coherent and frail joints,

at night was found as trash obstinately swept up

and hidden behind the door.

– This is the fate of any utopia,

to disappear one day into its own trash,

to be forgotten and hidden

like a shameful disease;

to die in its own vanity

with joints of a doe,

coherent and frail,

– they came to soothe her

the beards of the wise.

But then she would slam the doors even more hastily,

leave the city behind

and hide her face even more

of any human form.

She would sit (for instance) at the crossroads,

her hair on fire

crushed to a pulp by the gurgling impotence

that gushed from her throat,

by the human-faced madness

in which she was required to be doe,

just doe

with coherent and frail joints.

trad. M. M. Biela

Kto jest poetą / Cine este poetul / Who is the poet

POSTED IN classic poetry July 13, 2023

Kto jest poetą / Cine este poetul / Who is the poet

poetą jest ten który pisze wiersze

i ten który wierszy nie piszepoetą jest ten który zrzuca więzy

i ten który więzy sobie nakładapoetą jest ten który wierzy

i ten który uwierzyć nie możepoetą jest ten który kłamał

i ten którego okłamanopoetą jest ten co ma usta

i ten który połyka prawdęten który upadał

i ten który się podnosipoetą jest ten który odchodzi

i ten który odejść nie może

Tadeusz Różewicz

………………..Cine este poetul

poetul este cel care scrie poezii

si cel care nu scrie poeziipoetul este cel care rupe lanturile

şi cel care se inlantuiepoetul este cel care crede

și cel care nu poate credepoetul este cel care a mințit

iar cel care a fost minţitun poet este cel care are o gură

și cel care înghite adevărulcel care cade

si cel care se ridicăpoetul este cel care pleaca

și cel care nu poate pleca

………………..Who is the poet

a poet is he who writes poems

and he who doesn’t write poemsthe poet is he who breaks the bonds

and he who binds himselfthe poet is he who believes

and he who cannot believethe poet is he who has lied

and he who has been lied toa poet is he who has a mouth

and he who swallows the truththe one who fell

and the one who risesthe poet is he who leaves

and he who cannot leave

trad. M. M. Biela

Copyright © 2024 by Magdalena Biela. All rights reserved.